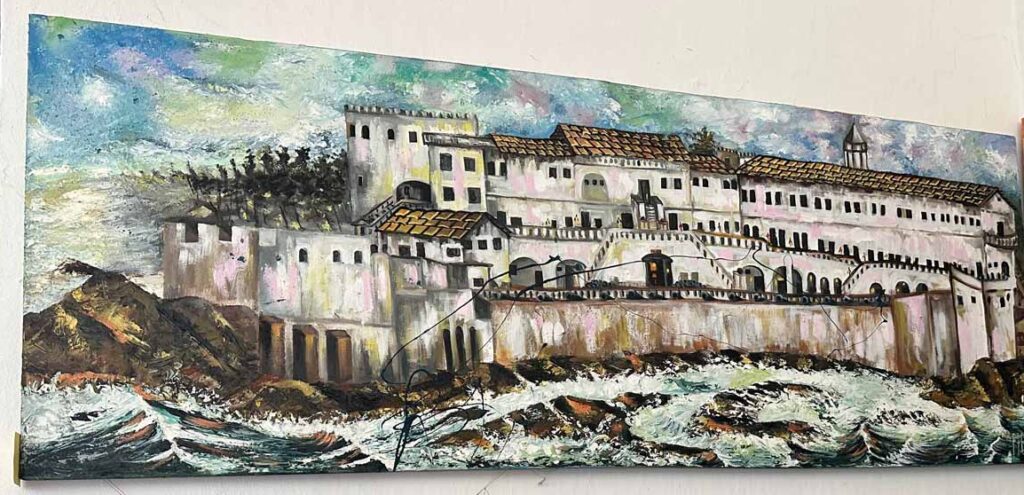

The bustling fishing village of Elmina lies along Ghana’s beautiful palm-lined coast. There, overlooking the harbor, sits the imposing, white-washed fortress of Elmina, once a major center for the Atlantic slave trade.

On my recent 2-week trip to West Africa, I was eager to visit this former slave fort – with its dark yet critical place in history. Even though my tour was focused on the region’s traditional tribal cultures, it included a visit to St. George’s d’Elmina Castle, one of Ghana’s most important visitor sites.

History throughout the ages is filled with stories of wars, conquests, and the subjugation of local people. When traveling, I feel it’s important to learn all about a place’s culture, its people and their history (positive & negative) – to deepen my compassion & better understand our complex world.

History throughout the ages is filled with stories of wars, conquests, and the subjugation of local people. When traveling, I feel it’s important to learn all about a place’s culture, its people and their history (positive & negative) – to deepen my compassion & better understand our complex world.

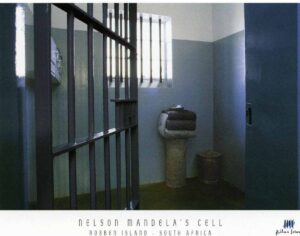

For example, I’ve toured Rwanda’s Genocide Museum, Cambodia’s Killing Fields, and South Africa’s Robben Island where Nelson Mandela was imprisoned for 18 years. These experiences were always sobering & powerful – and I was so glad I had gone.

Why This Blog Post

In the same spirit, I want to share my visit to Elmina – with a fascinating tour of St. George’s Castle (aka slave fort), followed by a walking tour of this delightful fishing town. First, a big thanks to my friend & travelmate Nadia Salameh for the use of many of her photos in this post.

Of course, modern society is still coming to grips with the global impact of slavery & the long dark history of the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade. For well over 300 years (from 1525 to 1866), between 10 million and 12 million Africans were sold into slavery. The majority came from West & Central Africa.

You can read about the brutality of slavery, but there’s nothing like standing in an actual African slave fort and seeing the dungeons where captives were kept in horrific conditions. That and hearing their stories was an incredible experience I’ll never forget. I echo these words from another visitor: In these damp dungeons, the unimaginable becomes real.

During my tour of Elmina Castle and through later reading, I’ve learned a lot about the global slave trade and its history. So, I will also share some key highlights I found particularly interesting – and I hope you will too!

Ghana’s “Gold Coast” & European Traders

First, in simplistic terms, it all started with gold! Turns out, 2/3 of the world’s gold once came from West Africa. Portugal’s Prince Henry the Navigator had learned about the land of gold & ivory beyond the Saharan desert. Thus, the first European explorers to arrive in West Africa in 1471 were the Portuguese in search of those precious items.

They arrived on the “Gold Coast” (precisely in the town of Elmina in today’s Republic of Ghana). The name Gold Coast had long been used by the Europeans because of the large gold resources found in the area, which were controlled by a variety of African kingdoms (like the Ashanti).

Desiring increased trade with the Africans, in 1481, the King of Portugal ordered the construction of a fortified trading post on the Gold Coast. The fort in Elmina was quickly completed in 1482.

News of Portugal’s successful trading spread quickly, and other European traders began to arrive, also building forts along the coastline. In exchange for gold & ivory, they offered goods such as guns, gunpowder, metal knives, beads, mirrors, and liquor.

St. George’s Castle in Elmina

The fort (aka Castle of Elmina) was named St. George (Sao Jorge), after Portugal’s patron saint. Rich with history, it was the first European settlement south of the Sahara. The castle/fort was first used as a warehouse to store gold & ivory, and eventually (and tragically) enslaved Africans.

The fortress was expanded when slaves replaced gold as the major object of commerce – and its storerooms were converted into dungeons. Thus, for more than three centuries, this castle/slave fort was one of the principal slave depots in the Atlantic Slave Trade.

Elmina Castle changed hands a few times. It was ruled by Portugal (1482-1637), Holland (1637-1872), Britain, and then Ghana when it finally gained its independence in 1957. And, like me, you might bristle at the use of the term “castle” but, in fact, that is the official name used for this large slave fort and others.

St. George’s Castle is the largest and oldest existing castle connected to the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade. It’s recognized as a UNESCO World Heritage Site, along with some other castles and forts in Ghana. It’s an important stop for regular visitors & those on slave heritage tours, seeking to discover their ancestral roots.

OUR TOUR OF ST. GEORGE’S CASTLE

On a warm February morning, we drove to Elmina from Accra, Ghana’s capital – a distance of only 100 miles to the west. Our mid-afternoon visit began with a short walk from our tour bus to the front of the bright white castle fortress, lined by tall palm trees flowing gently in the coastal breezes. It was a peaceful setting.

This large 97,000-square-foot castle was protected by thick fortress walls. We entered over a small drawbridge spanning a double moat (now dry) into the castle’s large main courtyard.

First, my group & I spent a few minutes in the small, but interesting museum housed in the former Portuguese Catholic church, which juts out into the courtyard (below right). We then met up with Richard, our excellent local guide who led us on a fascinating & sobering 1.5-hour tour of the Castle.

- Credit: Nadia Salameh (photo to right)

Richard told us the Elmina fortress could house over 1000 slaves. The African captives were held in dungeons for an average of one or two months. But it could be as long as three. It all depended on the availability of slave ships to take them across the Atlantic to their new enslaved lives in the Americas or Caribbean.

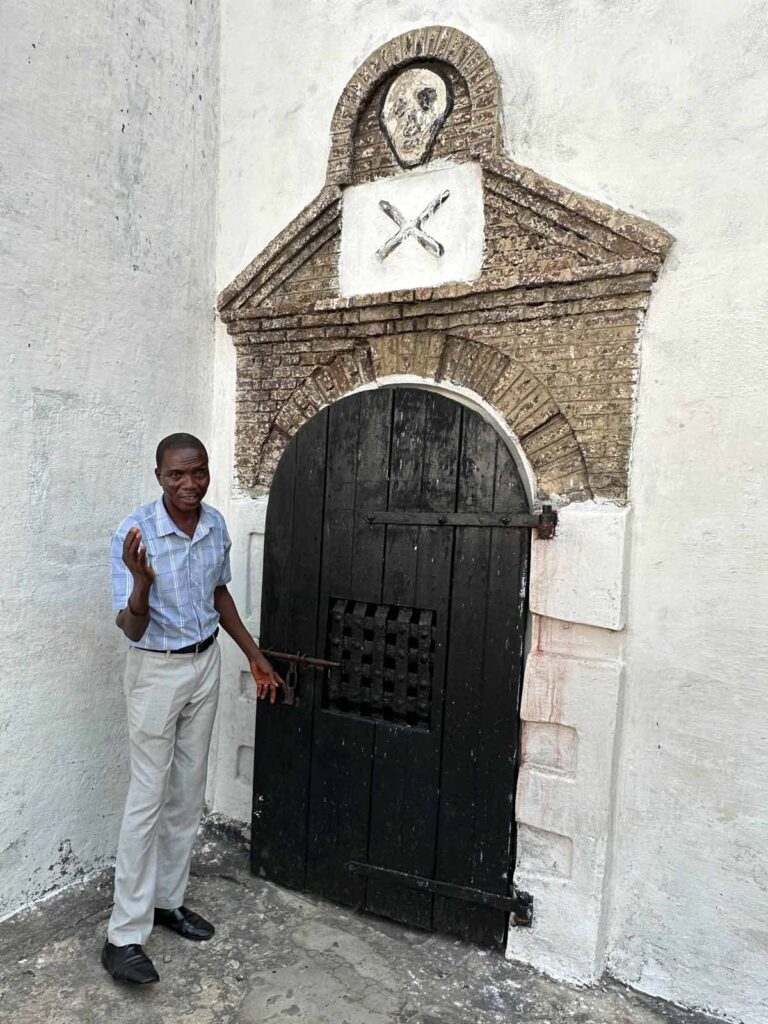

Courtyard & 2 Side Cells

In the main courtyard, all ground floor rooms were used as dungeons for the male captives. The exception was two smaller cells. One was a well-ventilated room for European soldiers who sometimes got drunk and misbehaved. (some things never change!)

- Credit: Nadia Salameh

- Our guide Richard

The second cell, however, was much more ominous, as evidenced by the skull & crossbones above the door. Condemned captives were sent here. Often, they were slave leaders who were caught fighting for their freedom. This small cell – with minimal ventilation – could be packed with up to 30 people. Prisoners remained there, without food or water, until they died. (photos below).

Life for the Captives

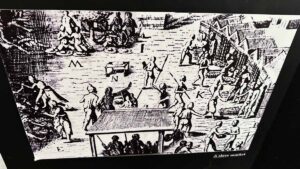

When captive Africans first arrived at the castle, they were examined for their age and health. Slave traders wanted to determine which prisoners were healthy enough for the long, arduous journey ahead. Captives were then taken to the dungeons – separating men and women. Family members would often not see each other again.

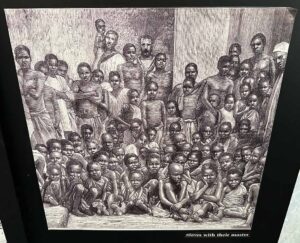

During the Portuguese era, captives were assembled in the main courtyard for auctioning. In the time of the Dutch, the Portuguese Catholic church (I can’t help noting the religious irony!) became the slave auctioning hall. Many captives were branded in various ways by their slave merchants.

As for the brutal conditions…Prisoners were given food and water, sometimes twice a day, but just enough to keep them alive. They were rarely brought out of the dungeons for exercise and sunlight. They were not allowed to wash – and were unable to move freely since they were in chains and chained to each other.

The Women’s Dungeons

- Credit: Nadia Salameh (both photos)

- Entrance to “Female Slave Dungeons”

From the main courtyard, we headed up some steps to enter a passage way that led to a small inner courtyard where women captives were kept. In the middle was a well, with a wooden cover.

- Credit: Nadia Salameh

Standing inside one of the adjoining dungeons, Richard told us how they housed 150 women here in crowded & shocking conditions. The dungeons had very few windows for ventilation or light. There were no toilets, just buckets in the corner of the large room. But with chains on their feet, it was often difficult for the captives to get to them. There may have been some straw, at best, on the stone floor.

- Credit: Nadia Salameh

One can’t even begin to imagine the unbearable heat and stench (from all the vomit, urine and feces) that the captives had to bear. It’s no surprise that the frequent abuse, living conditions, and near starvation caused the deaths of many of the captives. In addition, women (and likely some of the men) were subjected to sexual abuse by the soldiers, merchants and governors.

Richard told us the sordid tale of how the castle’s Governor would stroll out onto his balcony (two stories above) while women were brought out of the dungeon into the courtyard. He would pick out his next victim. She would be publicly cleaned up (with water from the courtyard’s well), dressed and brought up the special stairs to his residence – for the rape before being returned to the dungeon. Shudder… Such unimaginable cruelty.

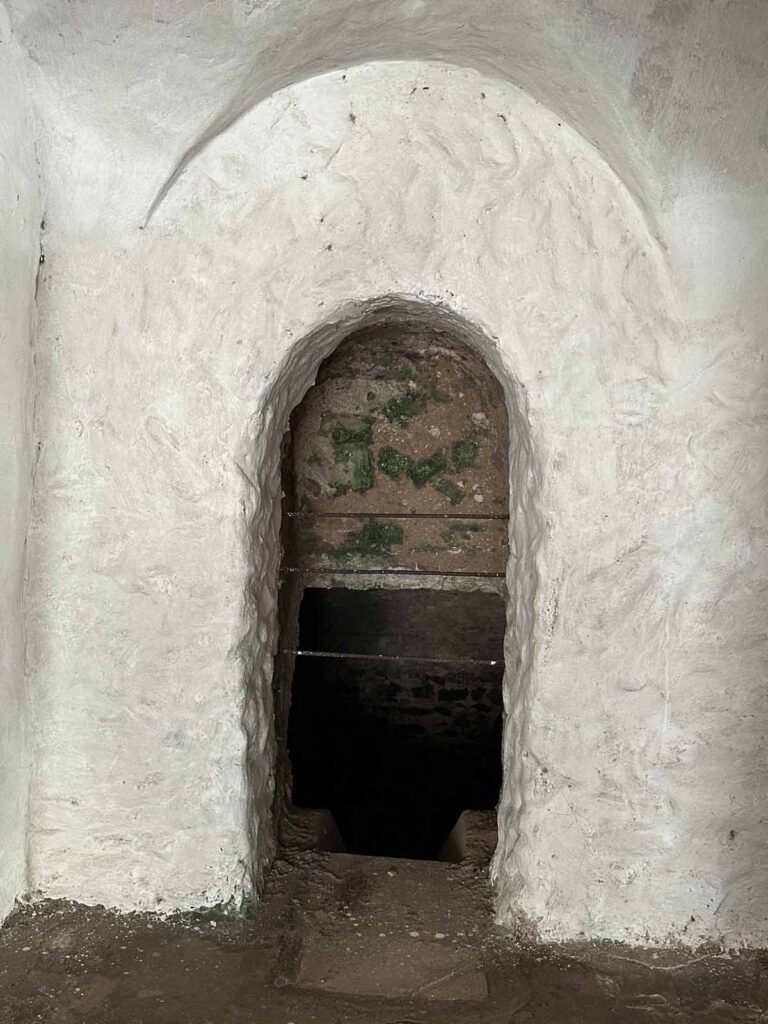

The Door of No Return

On our way out of the women’s area, Richard pointed out an arched window in the wall (below left). When the ships came and it was time to leave, women prisoners would enter here, sliding down a stone slide to the transit dungeon on the next level.

Here, women would meet up with the men – seeing them for the first time since their arrival. And sometimes, family members would be reunited. We entered this section from the main courtyard, under a sign that said Male Slave Dungeon.

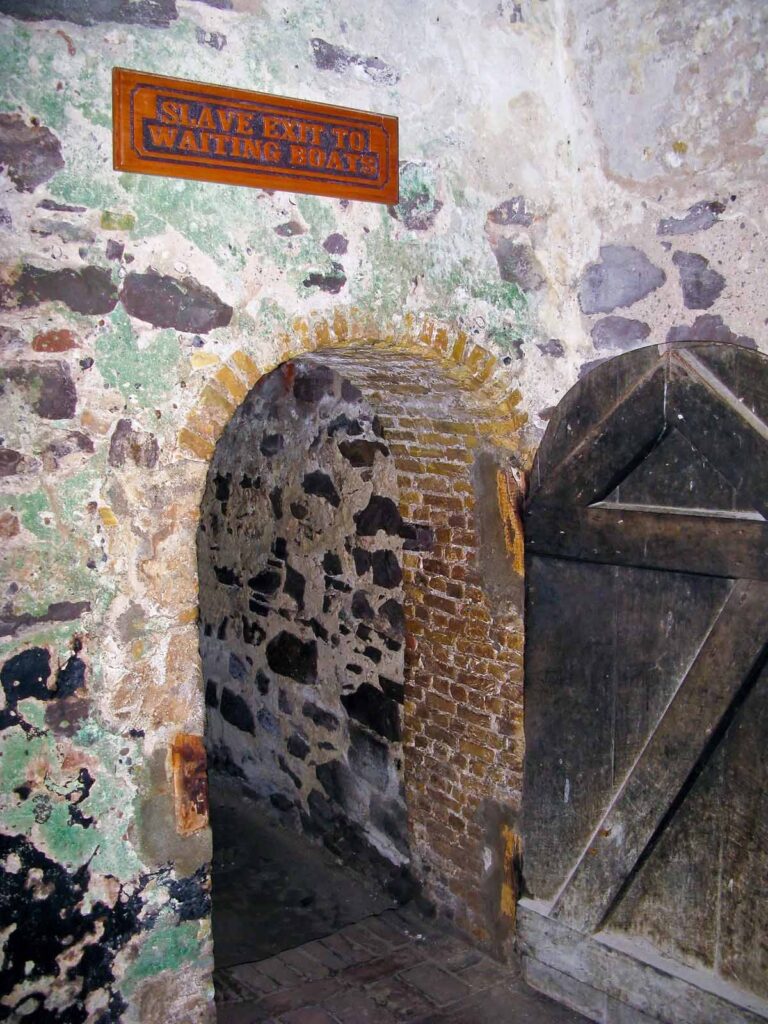

- Slave Exit to Waiting Boats / Credit: Deposit Photos

- Credit: Nadia Salameh

After passing through the room with the slide (above right), we had to squeeze through a narrow entry, by crouching down, before entering the final room. On the east side was the infamous, narrow “Door of No Return” (with its swinging iron gate). There, one by one, captives in chains would head out of the fort. Then they were taken in small boats out to the slave ships waiting a short distance away.

- Credit: Nadia Salameh

Thus, the enslaved Africans would begin a tortuous 2-4 month-long journey across the Atlantic to the Americas & the Caribbean. If they survived the journey, under incredibly oppressive conditions, they would endure a life of relentless servitude – for them & their successive generations.

- Credit: Nadia Salameh

- Credit: Nadia Salameh

In one corner of this dimly lit room, we could see some flower bouquets & memorial wreaths left by visitors in honor & memory of their African ancestors who had been ripped from their homeland & suffered so greatly. It made the experience even more poignant!

Upstairs Living Quarters of the Governor

From this area of darkness, figuratively and literally, we headed back out to the main courtyard. From here, we could see windows above the ground floor dungeons. This is where the living quarters of the soldiers, merchants and pastors/priests were located.

- Credit: Nadia Salameh

- Credit: Nadia Salameh

Richard led us up more stairs to the top of the castle to see the residence of the Governor. There, successive governors would live in relative luxury. We visited a couple spacious rooms with colorful painted walls & wooden floors, with large windows offering cool breezes & pretty ocean views. Quite a contrast to the living conditions of the slaves below.

- Credit: Nadia Salameh

Walk Along the Ramparts / View of Fort Jago

We also took a walk along the castle’s ramparts on the upper level, with views back down into the courtyard & out to the sea. On the north side, framed with 12-foot-long old Dutch cannons, we took in the picturesque views of the town of Elmina and its bustling harbor below.

- Credit: Nadia Salameh (left) /Deposit Photos (right)

From the ramparts, we also got a good view of Fort Jago, sitting on a tall hill above the town, directly across from us. The Portuguese first built it as a chapel in 1558, dedicating it to St. Jago. It later became a small fort (also known as Fort Coenraadsburg) in the 1660’s to provide military protection to St. George’s Castle.

Fort Jago is also a UNESCO World Heritage Site, with similar white-washed walls and red-tiled roofs. Today, it’s open to visitors as a museum and historical site. We didn’t have time to visit but apparently, it offers excellent views of the town of Elmina and St. George’s Castle.

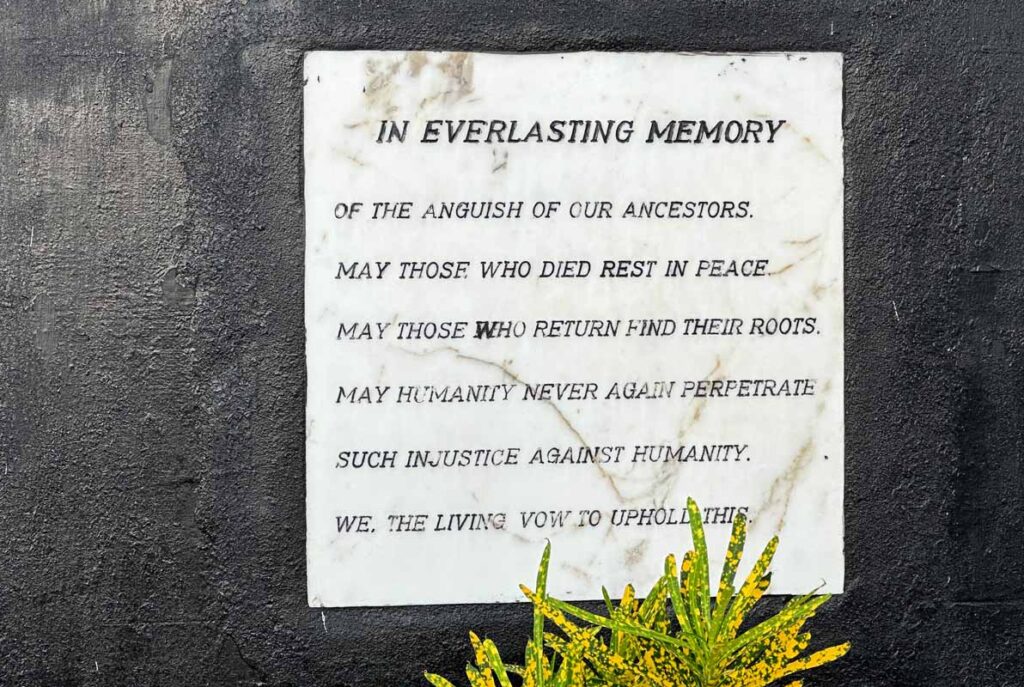

Castle Departure – The Eternal Vow

Returning to the main courtyard, we saw a large group of older Ghanian school children in their purple uniforms. Whether African or American (like my group), it’s important for all of us to know about this long, horrific chapter of our global history. We departed the Castle after giving our heartfelt thanks to Richard for sharing this powerful experience with us.

These words inscribed on a marble wall plaque next to a prison cell (above right) says it all.

IN EVERLASTING MEMORY

Of the Anguish of Our Ancestors.

May Those Who Died Rest in Peace.

May Those Who Return Find Their Roots.

May Humanity Never Again Perpetrate

Such Injustice Against Humanity.

We, The Living, Vow to Uphold This.

WALKING TOUR OF ELMINA

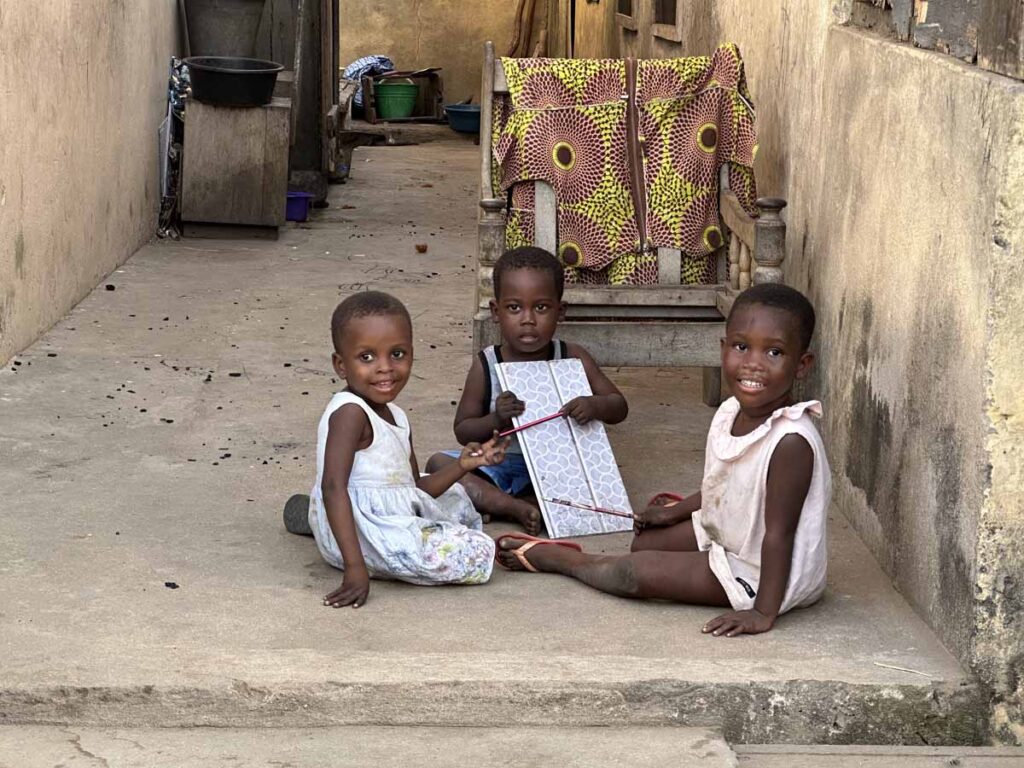

After touring the castle/slave fort, it felt good to return to happier times in present day Ghana. Just outside, we were met by Peter, a charismatic resident of Elmina. He was there to take us on a walking tour of his delightful town (population ~25,000) for the next hour.

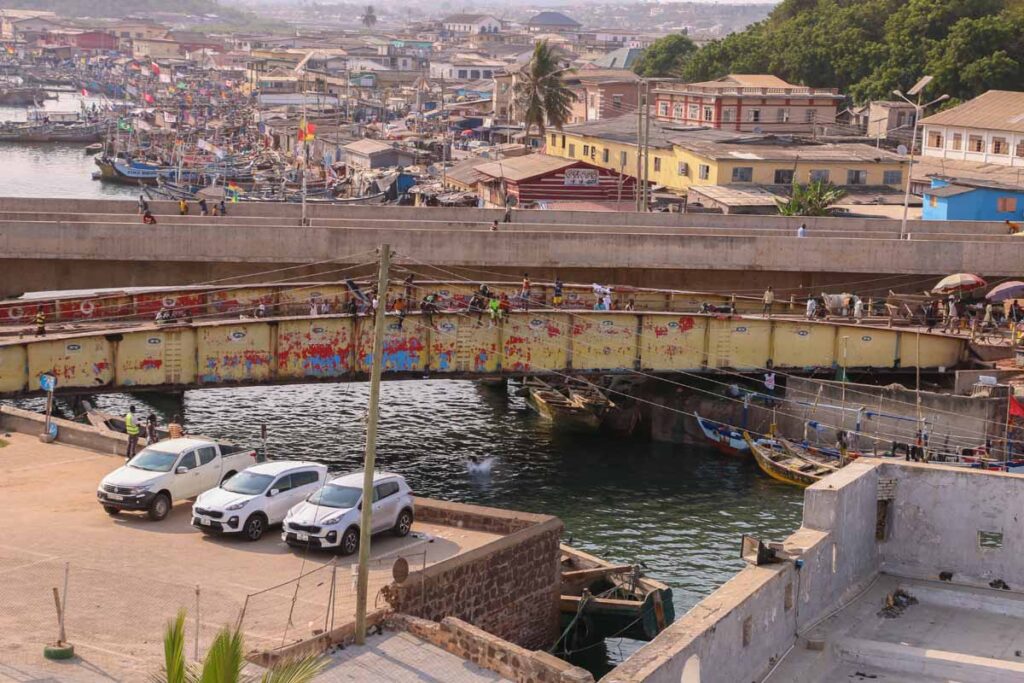

From the fortress, we headed down a short hill to walk over the main bridge which crossed the Benya Lagoon. In the past, the people of Elmina were predominantly farmers. But today its economic mainstays are salt-making and especially fishing, thanks to the town’s coastal location & its natural harbor.

From the bridge, we viewed Elmina’s picturesque fishing port lined with scores of brightly colored wooden fishing boats. Some of the artistically painted boats displayed religious names on their bows (the majority of Ghanians are Christian & quite devout!) and many flew colorful flags from different countries. However, I never learned the reason for the flags.

Peter proudly told us the fishing boats are actually owned by the town’s women! However, it’s the men who do the fishing – at night. They generally leave each evening around 6pm, returning early in the morning to sell their catch at the dockside fish market (on the south side of the lagoon).

Since we were touring in the late afternoon, we didn’t get to experience the hustle and bustle of the fish market. Too bad – that would have been great fun! Apparently, the traders – almost all women – buy the fish and carry them off in large woven baskets carefully perched on their heads.

Elmina Town Views

After crossing the bridge, we walked into town along some of Elmina’s lively streets with their charming mix of old colonial & African buildings. We particularly enjoyed watching the friendly residents going about their daily business. This included men repairing their fishing nets and young women doing “open-air” sewing. My photos will tell you more…

- (Left) -community freezer for storing fish / above – men repairing their fishing nets

Peter also bragged that Elmina, being such a fishing town, has many great boat makers. The wooden fishing boats are operated by between 10-20 men – and all have outboard motors.

On the way back to the Castle, we walked along the lagoon for a close-up view of some of the fishing boats. Men were lounging and/or preparing before heading back out to sea in a little while. Again, I would have loved to have been in Elmina in the morning to see all the boats returning from the sea, laden with freshly caught fish.

After saying a warm goodbye to Peter, we headed off for a short ride to our night’s lodging in Elmina. We all felt grateful to be staying in a nice beach-side resort (with the calming sound of waves) where we could begin to process all that we had seen & experienced today.

One More Important Site – Cape Coast Castle

As you’ve heard, Ghana’s Gold Coast was once the epicenter of the slave trade. Here, the Portuguese built more than 40 castles and forts as holding places for enslaved Africans. Cape Coast Castle, one of the most well-known slave castles, is also a UNESCO World Heritage site.

Unfortunately, we did not have time to visit Cape Coast Castle, but I want to make sure you know about it. Because, if your schedule permits on a trip to Ghana, I would definitely recommend visiting both castles for an even deeper & varied experience. Please make sure to allow time to explore Elmina and its colorful fishing port.

Cape Coast Castle was built by the Swedish in 1653. As many as 1,500 captives were held in the castle’s dungeons. Today, the Castle hosts a museum on the history of slave trade.

The town of Cape Coast is located just 13 km (8 miles) east of Elmina. It was the British commercial and administrative capital of the Gold Coast until 1877, when Accra became the capital.

MORE ABOUT THE TRANS-ATLANTIC SLAVE TRADE

(credits listed below for this good information)

The Portuguese started what has become known as the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade. Between 1538 and 1600, they began to transport slaves in great numbers to work on large sugar plantations in Portuguese colonies across the Atlantic (including present day Brazil).

By the 17th and 18th centuries, other European nations (particularly England, Spain, France and Holland) had established colonies in the Americas. They were growing sugar, tobacco, cotton and other crops. Huge profits depended on slave labor so the demand for African slaves was insatiable.

Exact figures are impossible to come by, but it’s estimated that from the end of the 15th century until around 1870 (when the slave trade was finally abolished!), as many as 20 million Africans were captured. Many of them died – some while waiting in the slave forts, but mostly from the brutal conditions on the ships and the New World plantations and mines. (Lonely Planet)

Here are a few other statistics I got from credible sources, just to round out the picture (knowing that these numbers can only be rough estimates and may vary a bit (regardless, the numbers are HUGE):

- For well over 300 years (from 1525 to 1866), between 10 million and 12 million Africans were sold into slavery. (a repeat from National Geographic)

- The British were responsible for 50 per cent of all enslaved Africans – roughly 3.4 million people – shipped from Africa to the Americas between 1662 and 1807. (Elmina Castle book)

- Over its four centuries, Portuguese vessels would carry an estimated 5.8 million Africans into slavery. Most went to Brazil — a Portuguese colony until 1822. (Elmina Castle book)

How Did Europeans Get the Slaves

In the past, African tribal kings would wage war on their neighbors, to gain more land as well as captives as the spoils of war. Over time, some of these kings began to grow rich by selling these captives to the Europeans.

In most cases, European traders encouraged Africans to attack neighboring tribes and take captives. They were brought to coastal slaving stations and exchanged for European goods such as cloth and guns.

The other ways included Europeans themselves capturing Africans and by African slave raiders. These African raiders would capture Africans, sell them to African merchants, who would then sell them to the Europeans.

When a person was captured, he or she would often have to travel long distances – sometimes over 300 miles to get to the coast. The captives were put in chains and forced to walk sometimes for months, usually barefoot. So, with little food or water, they would arrive at the coast extremely weak and sick.

Middle Passage – Brutal Life on the Ships

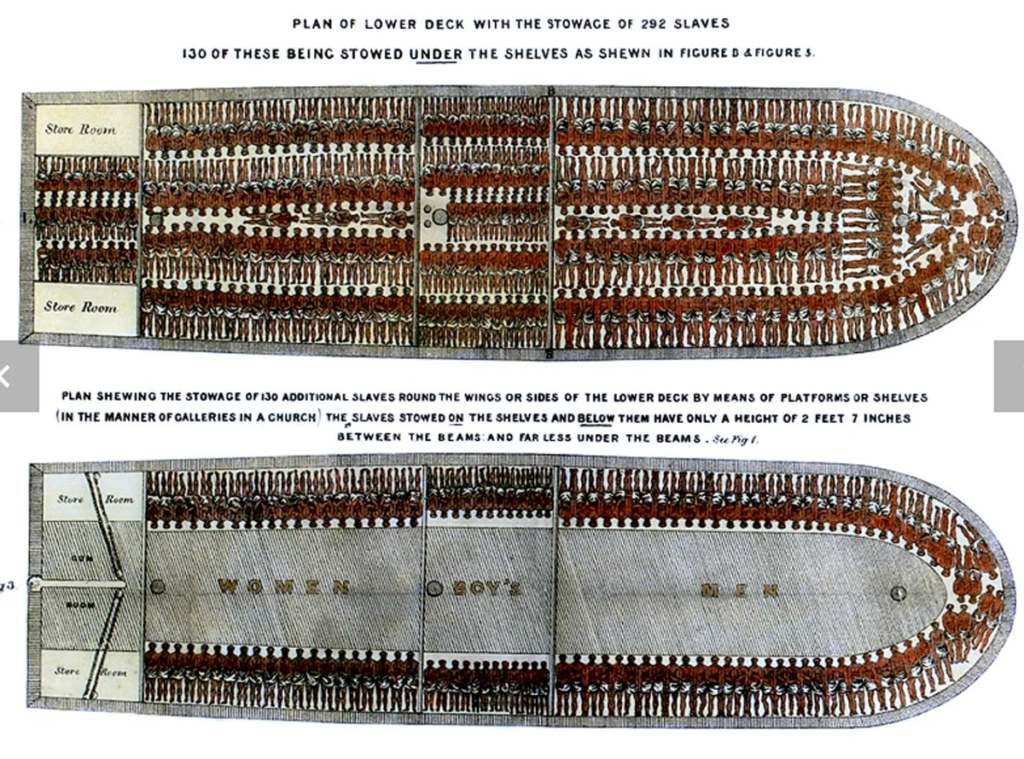

The term “Middle Passage” describes the journey of African captives from the places where they were being held (like coastal slave forts) across the Atlantic Ocean to the Caribbean, North & South America. The journey would average 3 months but could be as short as six weeks or as long as 4 months.

The Middle Passage was notorious for its brutality and the overcrowded, unsanitary conditions on the ships. In fact, the death rate for slaves on the ships was shockingly high. Historians estimate that between 15 and 25 percent of enslaved Africans bound for the Americas died aboard slave ships. (Britannica)

The captives were packed tightly into tiers below decks and were typically chained together. The almost continuous dangers they faced included epidemic diseases, attack by pirates, and the physical, sexual, and psychological abuse at the hands of their captors.

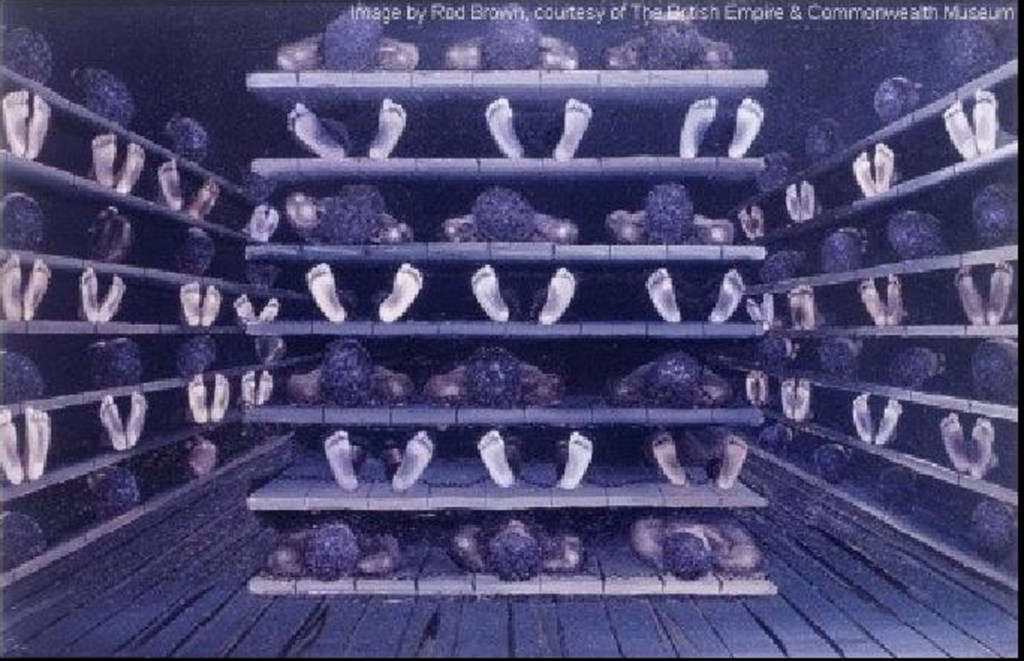

- Credit: Britannica website

- Credit: The British Empire & Commonwealth Museum

I was particularly shocked to learn that in the captives’ holdings on the ship, spaces could be just 20-25 inches high. Captives would lie side by side, unable to move and sit up – with their hands and legs in chains or shackles. I can’t even begin to imagine how horrific…

Abolition of the Slave Trade

The legal Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade reached unprecedented levels in the late 18th century, but by the mid-19th century every national carrier in Europe and the Americas had formally abolished the trade. However, the illegal slave trade continued until it stopped in the 1880s.

In 1803, Denmark-Norway became the first European country to ban the African slave trade. The United States followed suit in 1808, Portugal in 1815, Spain in 1817 and Brazil in 1825.

The U.S. 1808 federal law stopped the legal flow of new Africans into the country. However, slaving continued on an illegal basis for the next fifty years – such as slavers stealthily using whaling boats. Of course, the practice of slavery – for those already in the country – legally continued in much of the U.S. until finally being abolished in 1865.

In 1807, the British Parliament made it illegal for British ships to transport slaves and for British colonies to import them. And, in 1834, Britain passed the Slavery Abolition Act, outlawing the owning, buying, and selling of humans as property throughout its many colonies (the British empire) around the world.

KEY BACKGROUND SOURCES THAT I USED:

- Lonely Planet – West Africa

- Book I Bought at the Castle – Elmina, The Castles and the Slave Trade – by Ato Ashun

- Britannica website – a lot of good info on the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade

- National Geographic article – list of 9 memorials (including Cape Coast Castle) that trace the global impact of slavery

In addition, here’s the link to an interesting 6.5-minute CNN “Inside Africa” video entitled “Stepping Through Ghana’s Door of No Return.”

Sadly, we know that many different forms of modern-day slavery & social injustice still exist today, all around our world. May we & our collective human family continue to work to create a world where all people are treated with the respect, dignity & equality they deserve.

In closing, I want to repeat the Elmina Castle plaque’s powerful words.

IN EVERLASTING MEMORY

Of the Anguish of Our Ancestors.

May Those Who Died Rest in Peace.

May Those Who Return Find Their Roots.

May Humanity Never Again Perpetrate

Such Injustice Against Humanity.

We, The Living, Vow to Uphold This.

COMMENTS: Have you visited any of Africa’s slave forts? Which ones? How was your experience?

Post a Comment